Harold Bloom: “Somewhere in the heart of each new poet there is hidden the dark wish that the libraries be burned in some new Alexandrian conflagration, that the imagination might be liberated from the greatness and oppressive power of its own dead champions.”

The Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864 – 1916) painted moody portraits of his apartments in Copenhagen. His art teacher was Niels Christian Kierkegaard, the cousin of the philosopher. Hammershøi often depicted the same rooms and often painted his wife Ida as a contrasting silhouette to the earthy, airy, monochromatic reflections of light and shadows. He was the inheritor of the Dutch and the precursor to the Americans Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth.

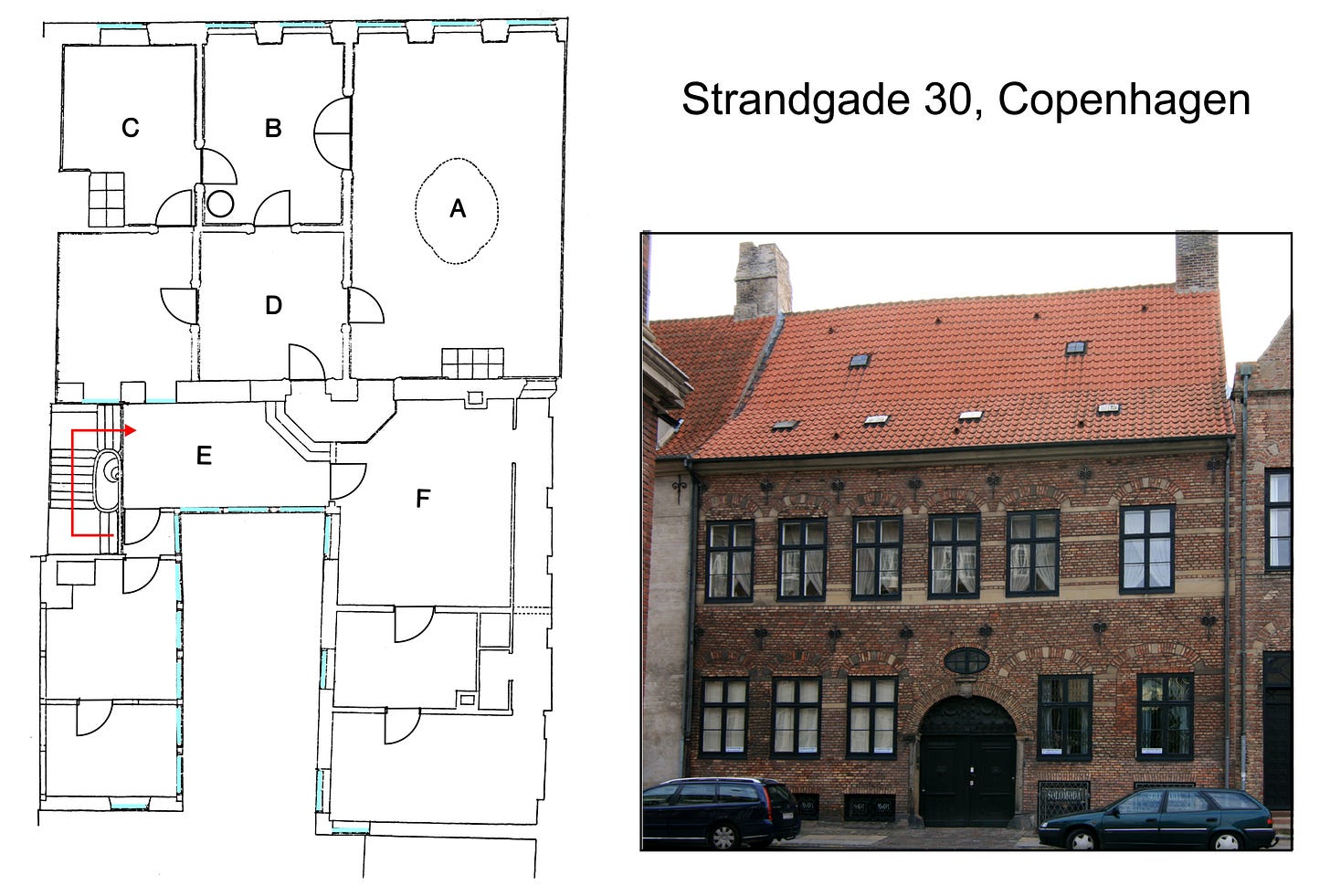

Vilhelm Hammershøi lived with his wife Ida at 30 Strandgade from 1898 to 1909, and at 25 Strandgade from 1913 to 1916. He died at fifty-two. His frequent subject at 30 Strandgade was this door and the Parlor window.

Sunlit Hammershøi Window No. 1

A single window can frame the light and add a dimension to a space that transcends the immediate function of a room. Those traditional muntins, mullions, or grilles are the leftover from the time when you can only manufacture the small panes of glass. But they are essential to the interior or exterior scale of a house. Modern glass manufacturing liberated glass from its limiting frame. Now the enormous, shapeless panes of glass create the oppressive glare outside and cheat a person away from the innate, protective need for the interior shelter. The large panes of glass are the curse of the modernity, they conspire with the tyrannical glare of the polished and the unnaturally smooth surfaces.

Dust is an essential element of a properly lit house. It invites the symphonic light. The lines that you see to the right of the window in front of the door are the shadows piercing through the dust. After the light crosses the dust, it is again reflected a second time on the floor. This one is the only Parlor window portrait where you can see the Spanish red clay roof shingles on the opposite side of the courtyard.

Hammershøi House on 30 Strandgate St. in Copenhagen

The window that is a theme of this post is to the right and at the right angle from Ida’s window. So, the door to the right of the window in the paintings, is the door to the bridge gallery where Ida is standing in the photo. Even when Hammershøi is outside the frame of his paintings, his connection to Ida is present and electric. In this photo Ida is a painting on the wall. Her head is tilted slightly in a saintly pose, she is looking at Vilhelm. It takes bold imagination to stage a photo so theatrically. On the other hand, a reenactment after years of painting exactly this.

Above is the depiction of the same courtyard. But Vilhelm is looking on the wall on the opposite side of the courtyard. He is looking from the Parlor window.

Shades of Vermeer, the strongest Hammershøi influence. More than shades… Again the woman is connected in a moment with someone on the ground. Masterfully he found so many tone variations on the dark surface. A beam of the prophetic light hitting the corner windows. This painting is so beautiful.

Hammershøi is paining the Parlor Window and Door in Room F, to the right of the Second Floor Bridge Entry Gallery E and below the Grand Room A.

Too bad they put the new windows on the house exterior, the courtyard windows appear still intact (BBC Palin’s film). Changes in the grille pattern alter the scale of a house. People often think that all windows are a commodity. There is no other building element on the exterior or interior of a house as impactful as windows. The original windows were painted earthy brown on the outside and white on the inside. To the right of the gate there is a remnant of a brick arch lintel that overlaps the window and the gate below it. There must have been a special opening there.

Moonlit Hammershøi Window No. 1

This is one of the moonlit paintings of the window. It has a pinkish hue. The beam of light highlighting the dust is now reversed to the outdoors. It obscures the other side of the interior courtyard that is now dark. The light doubly reflected off the moon and then off the floor to light up the interior walls. Hence, the bottom of the wall and the door are lighter than the top. There is an impression that we are looking at a translucent, flat screen. Or a throw of a patterned, unified in color and design fabric. There are no decorative elements on the walls or the floor. Like the first painting above, this one is a naked meditation with no accessories.

Sunlit Hammershøi Window No. 2

Ida is in silhouette. Hammershøi throws curtains on the window, so the light doesn’t overpower. One of the elements of the paintings and the apartment are the traditional mouldings that shape and frame the wall surfaces. Here Hammershøi hangs two identical pictures on the wall to support the composition and to rhythm the glistening reddish-brown furniture stain. He is not going to show superfluous faces even in the imaginary portraits, they are just an oval blur. He doesn’t need a face to show the moody, intense, fatalistic Ida. She might be reading, praying or thinking, but she is linked to Hammershøi in the severe meditation of the condemned soul. The door is askew, contrasting the weightlessness of the light with the unbearable gravity of the house.

There is the premonition of death. And the soul flying through a window before circling over the Hamlet’s castle in Copenhagen…

Sunlit Hammershøi Window No. 3

Above is a rare facing Ida, actually reading.

Moonlit Hammershøi Window No. 2

Here Hammershøi almost recycles his old painting to experiment with the window. Unlike most other paintings where colors on the interiors and the window blend, this window has the distinct glowing green color. Hammershøi covers the top of the window overlooking the roof with the short curtain dress, to make the window body appear more homogenous and radiantly translucent.

Sunlit Hammershøi Window No. 4

Ida is sewing, again the rare facing portrait. Hammershøi experiments with the opaque framed paintings that are similar in size but contrasting in texture to the transparent and glowing window grill. There is the geometric confinement and the smoldering embers.

Moonlit Hammershøi Window No. 3

This is a moonlit window. The palette is consistent. Dark green brownish hues. This is the only Parlor painting where Ida is looking through the window. Ida never actually stands in front of the window which would be too banal and too obvious for Hammershøi. The window is an alive object, and it requires its space. Do we really know if Ida is staring through or at the window?

Candlelit Hammershøi Window No. 1

The same window at night. The man might be Svend Hammershøi, the younger brother. The glass reflects the candlelight. Earthy brown and greenish tones. The door handle now a round, perl-like jewel mirroring the light.

At night the tonality is much more subtle and deliberate. The front corner of the table floats reflective light above the deep brown shades on the floor. Unlike the first daylight paining where the floor restrains the lit dust in an intense glow, this nighttime light dissolves into a muddy and opaque firmament.

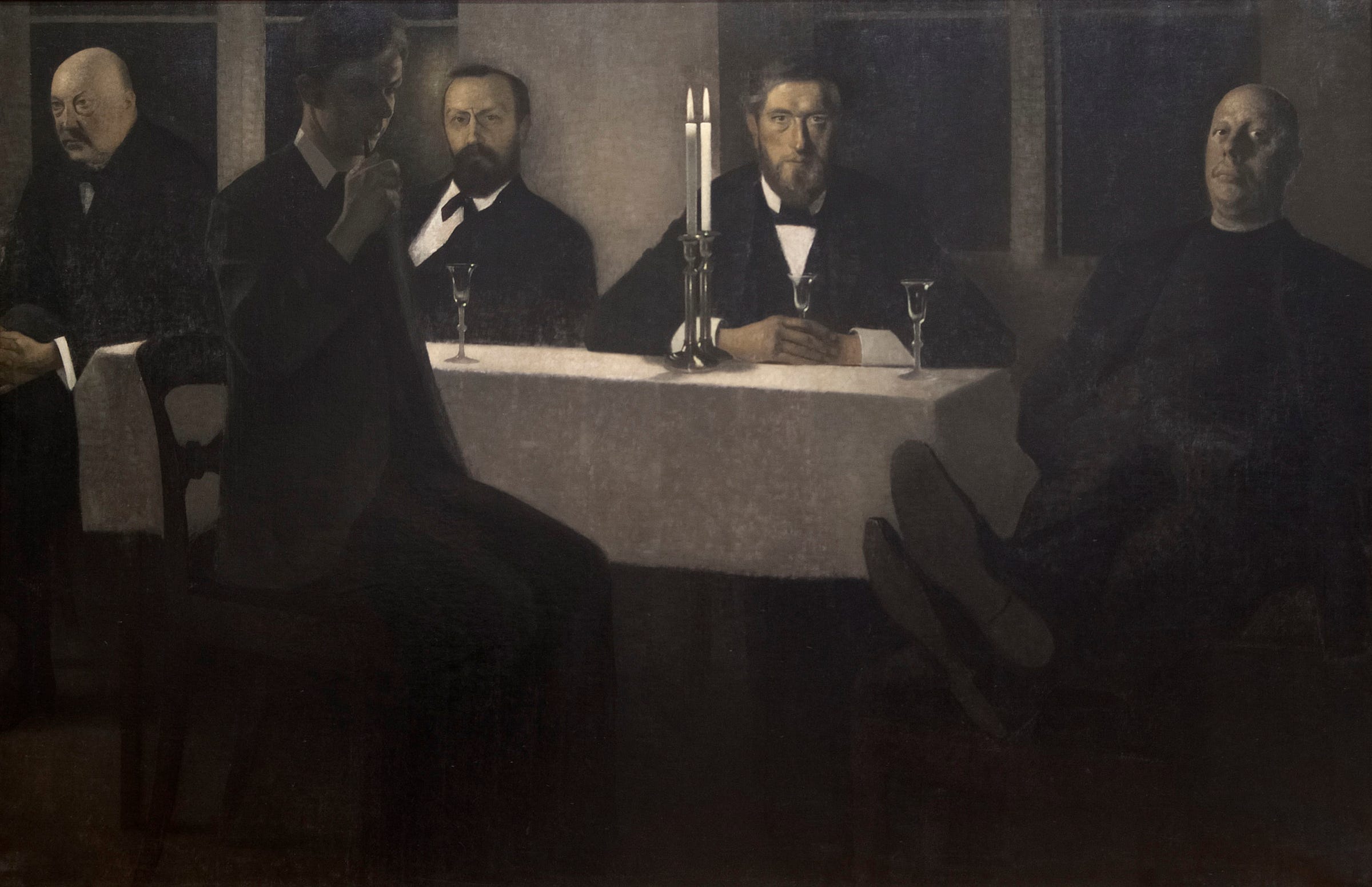

There are the same two minimalistic candles that later star in the Five-Man portrait (below).

Moonlit Hammershøi Window No. 4

The painting is from Tate museum. This is another moonlight, but very different in hue. This one is yellowish brown, a more realistic departure from the grayish tones. Closer to the patina of the historic oil paintings but further away from the Hammershøi palette. In the reflected moonlight, the bottom of the walls is highlighted. But there is now more depth to the composition with the other side of the courtyard visible through the glass.

The white muntins that are light against dark glass in the sunlit windows are dark against light in the moonlit windows. This setting introduces the white tablecloth covered table. Perhaps as a relief for the brown earthiness of the room and the grounded tonality. Originally, there was another Ida sitting by that tablecloth, but Ida’s side of the canvas was wrapped, disappeared around the frame by the artist.

One can spend a lifetime meditating a single properly lit window. Harold Bloom suggests seeking your shadow, and shying away from the reflected light.

I know why Ida had the most famous neck in Copenhagen. It was too intense for Hammershøi to see straight into her eyes. Even when he paints Ida’s face, he hides her eyes in a book or sawing. How can you stare at the face on top of the mountain? How can you see and live? When objects animate with spirits like the sorcerous Parlor window, when even the fleeting shelter feels the unbearable fate of the destined departure.

Hamlet: “the rest is silence”

Excellent!

Please explain these two sentences near the end:

"One can spend a lifetime mediating a single properly lit window. Harold Bloom suggests seeking your shadow, and shying away from the reflected light."

Am I right in reading the first of these two sentences as "One can spend a lifetime meditating on a single properly lit window"?

With regard to the second sentence, I'm guessing that Harold Bloom means something along the lines of "do your own thing instead of imitating some great person from the past" -- is that correct? If so, how should this advice be connected with what you're writing about in this essay? Wouldn't Vermeer be the relevant great person from the past? Or do you see this Danish painter as a great person from the past whose light a person of today might be tempted to reflect?

This is excellent. Thank you!