Gerard Menuhin -“Lived it Wrong” in the Flat Circle

Forgotten Alter Rebbe's and Berdichever Einiklach

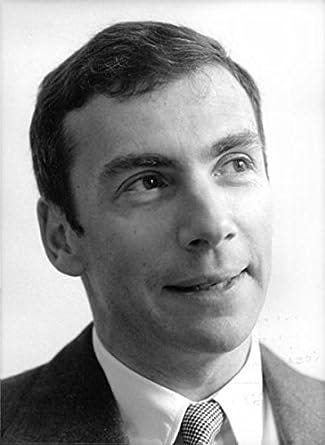

In the previous post, we described Moshe Menuhin and his yichus. Gerard is the grandson of Moshe Menuhin and the son of Yehudi from his second marriage. He wrote the autobiography, one can relate to the title. When I bought this book, Amazon immediately suggested another book by Ron Unz. Hey Amazon AI, Ron Unz is also a “Holocaust denier”, but at least he is definitely Jewish… “Holocaust denier” is really as smear. Of course, Gerard doesn’t deny the Holocaust, he argues with statistics and causes.

In the past five years, there has been weaponized propaganda and outright lies that at this point I am reluctantly inclined to revisit every “self-evident” assumption. Everything is a lie until proven otherwise.

In this book, besides the two paragraphs of the praise for Hitler, not much on Gerard’s revisionism, mostly events and contemplation on facts of his personal life. Being sober about Jews is not a revisionism, it’s a moral stand of a thinking man. Especially in the times like ours, when not all but the majority of the still calling themselves Jews, actively support the dictatorial and censorious institutions of the dark power.

Gerard’s autobiography is a bitter account. All quotes are from this text:

“This book is an attempt to explain myself to myself.

How did I become who I am?

My brother confides: “I would have far preferred you to have committed murder than espouse those views.”

I belong to an almost extinct race: the individual.

People who act in groups embarrass and repel me because they lack independence. People who think in groups are even worse. They have voluntarily rejected that part of their bodies which raises them above animals: the mind [copy/paste, Tanya]. They have repudiated their ability to think for themselves. Obviously, Creation was much too generous in its distribution to humanity of brains, as most people can’t find any use for them.

This general mindlessness has helped those who depend on lies to further an abominable system. Liars are inferior. I abhor inferiority. So I automatically rebel against any system that has been devised to benefit inferior people.

I didn’t recognize my own conformity within this system until very late in life. During my tortuous development, I struggled through various incarnations, in film, in foreign trade, in literary composition, in environmental job-creation, in journalism, before recovering my identity as an individual. At the moment, my individuality as a historical revisionist has resulted in my becoming a member of an endangered species, and in my relatives considering me to be mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

Those Schneersons, all passionate scribblers and writers. Manipulators of language and manipulators of people who are obsessed with language. I hear the notes of Alter Rebbe’s elitism. But, how lucky, Gerard never met the members of the movement that his great-grandfather started.

Revisionism

Gerard’s revisionist work about the Jewish history and the Holocaust is Tell the Truth and Shame the Devil, published in 2016. It’s not available on Amazon or any other “official” bookstores. Guess who is the devil? Not the Germans, to whom the book is dedicated. But this post is only about Gerard’s autobiography “Lived it Wrong!”

The Grandfather Moshe Menuhin

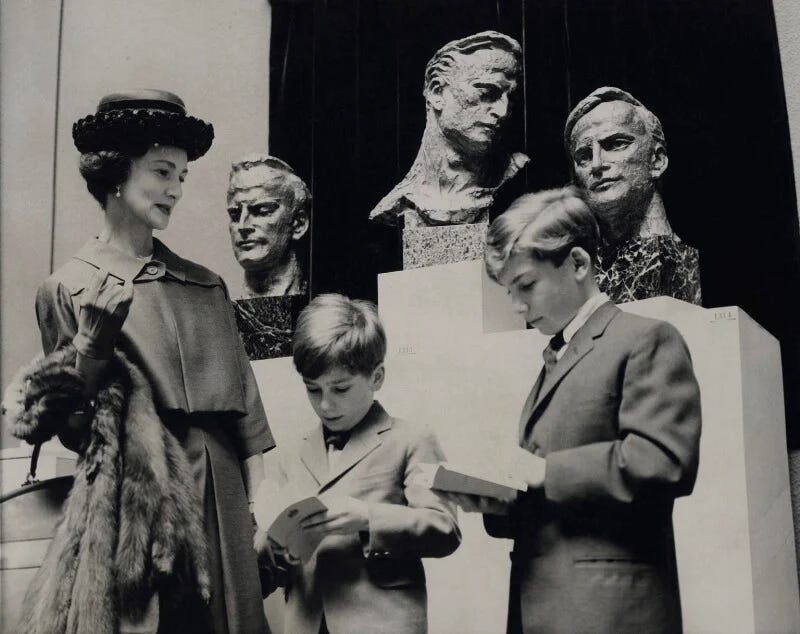

Little Moishelle Menuhin, one day he farbengs with his uncle Sholom Ber Schneersohn in Lubavitch, next day he's celebrating Christmas on his 300 acres property in Los Gatos. Los Gatos in Santa Clara County is on the outer edge of what will become the Silicon Valley. There Moshe Menuhin writes his books. There, Gerard spent his early childhood until his was shipped out to a boarding school.

At least the Rashab would agree with the first title. Probably with the second as well. But I don’t know, Moshe is not very strong himself in the betrayal of Judaism department… And speaking of “decadence”, 300 acre villa in Los Gatos at the same time as Shoa and Gulag?

Gerard writes that his grandparents unexpectedly discovered a golden egg in their nest, and gave it all the nurture.

In the Summer of 1983, after receiving a very critical letter from his father Yehudi, Gerard remembers: “My father resembles his father in that, when upset, he discharges his opinions and judgements in an angry stream, his handwriting almost illegible. His thoughts are apparently unconsidered; certainly uncurbed. My grandfather would froth at the mouth, metaphorically speaking, when he spoke about the ultra-Zionist pioneers who first conquered Palestine, under and just after the British Mandate, the adherents of the Irgun and Stern Gangs, for instance, and described them as ‘dirty gutter Jews’. A child in pre-Mandate Palestine, he remembered the Arabs he had known then, particularly his dentist, as benevolent and pacific, and held the extremist Jewish pioneers to be responsible for fomenting hatred between Arabs and Jews. However, he could be just as vituperative about American politicians. No conversation about WWII was complete without the mention of ‘that sonofabitch Truman’. His anger translated into his prose, where five adjectives would do the work of one. His obsession with the wrongheadedness of Zionism found expression in his book The Decadence of Judaism in Our Time, which made him many Arab friends, and a few Jewish enemies.

As T.E. Lawrence is supposed to have observed, Semites have no half-shades in their register of vision, and are only at ease when they think in extremes. His son is scarcely more poised. To the public, he is the personification of peace and mildness, a practitioner of yoga and an advocate of reconciliation and harmony. At home, it’s another thing. He never comes right out and says it, but we are to conform to the environment he has generated. He is intolerant of deviation: what is good for him is good for us all. He is allergic to negativity: everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds. How he came to this conclusion is anyone’s guess. He has seen and experienced his share of horror and disappointment.”

Gerard responds to his father on June 9, 1983. He points out that he is the only Menuhin (and I would add most Schneersons into the pile) who held a job:

“You counsel me to ‘learn the ways of the world’. Consider please the fact that I am the only Menuhin to have known the contemporary world on a regular, nine-to-five basis. I have gone to work in all weathers, often unwell, usually by public transport, in three major western cities — in other words, I have lived as most people have to live. I have had to deal with boredom, frustration, bias, intimidation, mediocrity, etc., as you have never and will never know them, as no other Menuhin has known them. I have experienced some of the seamiest sides of humanity, and some of its ordinary best. In our family, I am uniquely able to speak of such things.”

Assimilation of the Mishpoche Schneerson

On the subject of our podcast: The Eclipse of the Schneerson Family. You can say it’s a theme of the mentalblog, the astonishing, rapid and complete assimilation of the Schneerson royal family. There is one thing about the Jewish royalty, Schneersons and other Rebbes, the sense of a noble duty to their subjects was very rare. Gone are the days when what it meant to be a king was to heroically lead your people into a battle. In the Chassidic model of “leadership”, the subjects only mattered when they provide self-appointed theocratic kings with a luxurious life of comfort. In a way, what is even the difference between Meghan/Prince Harry and Mendel/Musya Schneerson when they left the seat of the royal court as far as was possible to pursue “other opportunities”? It’s only accidentally that Mendel and Musya fell back into it. If not for the war, I could see them living out their intellectual, introverted lives in the refined and decadent European Paris.

We hear about one, two, three Schneersons that managed to pierce the iron curtain. Hundreds of the families that stayed behind perished without a trace. Or should I say without a Jewish trace. This history is not mentioned, not even known to the Chabad PR undertakers.

But I digress, sorry Gerard. If you are reading this, you don’t know how much we relate!

The Mishpoche of Yehudi Menuhin

Gerard is the son of the second wife of Yehudi. Wikipedia provides details of the assimilation (Yehudi himself Jewish?). All Moshe Menuhin’s children intermarried. “Yehudi Menuhin was married twice, first to Nola Nicholas, daughter of an Australian industrialist and sister of Hephzibah Menuhin's first husband, Lindsay Nicholas. They had two children, Krov and Zamira (who married pianist Fou Ts'ong). Following their 1947 divorce, he married the British ballerina and actress Diana Gould, whose mother was the pianist Evelyn Suart and stepfather was Admiral Sir Cecil Harcourt. The couple had two sons, Gerard and Jeremy.”

In his second marriage, Yehudi departed from those romantic and musical names, Krov (Russian or Hebrew?), Zamira to a proper Gerard and Jeremy.

Gerard has the “Schneerson memory”. Meticulous, even absurd details, chronologically from his childhood on. Absent, emotionally, uninvolved traveling parents shipping him out of sight to various boarding schools. Sensitive, self -reflective child left to his devises and hating it. Mixed identity, not only religiously. Schools in the US, Switzerland, England. Often extended travel all over the world. The sense of foreign loneliness, introverted disdain for the utilitarian, that underlines the failed relationships with women.

Gerard Menuhin married Eva Struyvenberg, she was like Gerard, “half European” and spoke German and Italian. They married in March 1983 in New York. In 1990, he and Eva had one child, Maxwell Duncan Menuhin, but later divorced. Gerard on the memorable phone calls in 1994:

On Christmas Day, I ring Eva and my son to wish them well. Her response: “Fuck off!” On New Year's Day, I ring Eva and my son to wish them well. Her response: “Fuck off!”

Father Yehudi Menuhin

Gerard writes about his father: “How did Yehudi ‘the Jew’ Menuhin respond to his gradual awakening to the undisguised Jewish nature when he discovered it? There is no evidence that he ever did discover it. Having grown up with only one driving impulse, music, in a nonreligious household, a household which revolved largely around himself, he had been free to develop his utopian mission, by which conflicts between peoples could be overcome by music, his music, undisturbed by the mundanities of life. Unlike most musicians, whose ignorance of all beside their profession and perhaps a hobby or two is always evident, my father regularly read the news and engaged in public affairs of all kinds. He also tried to mediate between the two sides in Palestine, for which he must be honoured, however hopeless such efforts may be. Certainly, audiences all over the world were impressed and soothed by the unmistakably pure tones of his violin, and responded to the nobility and sincerity of his bearing, as well as to his legendary generosity in favour of a multiplicity of causes. His heritage comprises many unique recordings, a world-famous, government supported music school, a programme for concerts in prisons and hospitals, a foundation for musically linked projects in schools (of which I was briefly head of the German chapter), and a wealth of good thoughts and sayings on general subjects. Above all, perhaps, 20 years after his death, his legacy of goodwill is still to be encountered, sometimes in unexpected places.

While still young and naive and politically uninstructed, he co-sponsored The Black Book (1946), a Jewish compendium of horrors allegedly committed against Jews by Germans during WWII. (Originally begun as early as 1942, it was considered to be evidence at the Nuremberg trials.) Whether or not he did this at the prompting of his agent, it was a logical conformity. He would not then have criticized the treatment of Palestinians in the soon-to-be created state of Israel, however often he might have heard his father inveigh against it. One of his most enduring habits was to ignore — to push under the carpet, as it were — anything that disturbed him. He must have been bothered by the enmity of New York Jews,

when they, who had, of course, come through the war unscathed, attacked him for his defence of the great German conductor, Furtwangler, and for backing him for the post of conductor of the Chicago Symphony. Untroubled by facts, by the evidence that Furtwangler had protected many Jewish musicians in his orchestras during the war; they found this an appropriate or even useful excuse to attack my father. On the one hand, the Italian conductor, Toscanini, wanted the position, on the other, my father had adversaries in the New York Jewish musical world, notably a violinist called Stern, who, in the manner of a coarse careerist, considered Yehudi Menuhin his rival, and led this attack from somewhere in the rear, motivated by envy of my father’s inspirational insights and general superiority. They bore him a grudge anyway because he had refused to join a

musicians’ union which planned to embargo foreign violinists from playing in the U.S. The New York Times, ever the primary medium for Jewish propaganda, reported on February 2, 1949 that my father’s concert in Rome had been boycotted by Jews and had therefore been half-empty (as though a few Jews could have had that effect), when in fact it had been so packed that a delegation of Jewish students who came to ask my father for free (of course) seats had to stand. This lie was followed by a regular campaign of slander by the U.S. Jewish press, asserting that Menuhin had dared to play on some silly Jewish holiday — in the UK. Not only had my father changed the date of the concert, but he had renounced part of his fee to placate the organizers. Presumably, my father had earned this Jewish persecution merely because he had stood up for Furtwangler and turned over his fee to German orphans, when he played in Berlin after the war.

My mother’s diary for 23 September 1949 records a dinner table conversation in Berlin with a Rabbi Schwarzschild, during which he recounted ‘his address in the synagogue in which he attacked the Jews for their anti-Semite-provoking behaviour’. New York, described by my grandfather as a ‘cesspool’, and the enormous void between it and the West Coast that is America (rather like the space between two ears, I always think), couldn’t compete with Europe’s sophistication and rich variety. Probably, this experience, added to my mother’s preferences, impelled my father to resettle in Europe, first in Switzerland and

then in London, which he had visited frequently during the war and which is, after all, one of the great musical capitals of the world.”

Lessons in Psychology from the “non-gifted” child, by Gerard Menuhin

“Relationships, like friendships, are modes of life that one acquires by practice. One has to learn them when young. I never learnt them. I probably didn’t fit my allotted role. I was certainly a disappointing child. I let both my parents down, never achieving what they doubtless expected of me. Maybe they discussed

my failures openly; maybe they lamented them privately. However, they brought my failure upon themselves, were the originators of it, by thrusting obstructions in my path. They were both, in their individual ways, extremely selfish and self-centred. My mother was probably dysfunctional like her siblings, and my father was totally concentrated on his interests and aspirations. His own self-disciplined, utterly undeviating and goal-oriented upbringing gave him no insight into or sympathy for the ordinary development and the self-doubts of normal children. Neither did it apparently occur to him that he had not been expelled

at an early age, from familial surroundings, as I had, and thrust into an adverse environment. Both my parents profited from knowing that I would probably come to no great harm at boarding school, at least physically, while learning my lessons, and they were thus freed from the distraction of the more difficult of their children.

‘Yehudi Menuhin: The genius who put the fight for justice before his family’ (The Times, April 6, 2016). My father was remarkably uninvolved in my development; he never showed any interest in my progress. Entirely ignorant of formal schooling, he left decisions about my education to my mother. I expect children bored him — unless they were musically gifted, as was my brother (now, a gifted pianist). However, he was an inveterate letter-writer, whether about politics to The Times, or about his uncooperative son. Recently, I came across a letter my father had written to the headmaster of my prep school in 1960, when I was 11. In it, he explains why, as a result of my disinclination to learn, I would be tutored at home.

This decision ‘seems to make sense for more reasons than one: his own nature in the first place, which is in all respects singular, both figuratively and literally, and has been starved since he was six of a continuous and unbroken contact with his own family, which before its next transition into adolescence should fill out these gaps in his personal experience with his parents and his home’.

This clinically disengaged view of my early years, recounted as if my estrangement from my roots were the result of an act of God rather than of my parents’ own will, or as if I were a laboratory experiment that had temporarily gone wrong, demonstrates my parents’ relations with their children. Neither of them could spare the time for us. Unless I fitted in with them, or at least showed unremitting sympathy for my mother’s grievances and emulated my father’s optimism, I was out of favour. But children are not innately hypocritical or intentionally obstructive. They do not mean to disappoint. Hypocrisy and rebelliousness are also learnt traits.

Children have a right to their parents’ time and support. Parents have the advantage of seniority, of their years of experience of life. They should instinctively feel sympathy and understanding for their own children. Instead, they often institute a kind of intellectual abuse of them, which starts with their own intolerance and provokes in their children a vicious cycle of misery obstreperousness-misery, which, in turn, provokes more intolerance.

Why did my parents have children at all? What was the point? My father had had two already, although his first son did not see him for about ten years, and my mother was far too self-absorbed to take her focus off herself. By the time I was seven and had experienced the initial desertion, I had probably already developed troublesome tendencies and had become a nuisance. (“Why did you engender me?/ We [I] didn’t know it’d be you.” Beckett, Endgame) It was therefore not only English custom, not only my mother’s English background, which landed me at an early age in a boarding school.

Another letter, this time addressed to my housemaster at Eton and dated January 1962, when I was 13, states ‘The sad thing is that he is actually very happy at Eton...’ In fact, I was hideously unhappy at Eton, at least during the first four years. So my father must have been describing some other person, or rather, modifying circumstances to suit his delusions. Like his own parents, an unbeliever, my father then goes on to write ‘It seems to me that if he were only old enough to have the kind of religious conversion which brings all the simple but basic qualities of humility and faith, his problems would be resolved forthwith.’ Almost 60 years later, I have still not emulated St. Francis: I am absolutely faithless, while appropriately humble.

My mother’s addendum to my father’s letter in the following year, again to my housemaster, contains the following illuminating remark: ‘I am so sad and disturbed… I feel rather sorry for him, where I used to feel anger.’ Where previously, the researcher had been angered when the guinea pig showed an unexpectedly rebellious disposition, now she was only saddened by this baffling phenomenon. My most outstanding trait is perhaps being able to make the least of every opportunity. The Pogo quote ‘We have met the enemy, and he is us’, whatever it may say about society in general when it refuses to face up to vital changes, accurately describes my association with myself. Since my earliest experiences of disappointment or mortification, I have always lived at odds with myself, detached from myself, at one remove from reality. Often, I cannot relate unequivocally to my being, to my body, to my own space in my environment, wherever that happens to be. There resides in me the doubt that I am entirely real. Being recognized is sometimes an unpleasant jolt, as I am convinced that I am not only utterly ineffectual, but practically invisible as well. This dichotomy of almost-being versus being is rooted in my childhood, when I believe I felt more than most children that I was the victim of arbitrary decisions, decisions contrary to my welfare.

So it was natural for me to seek solace in books. It occurred to me only recently how much the refuge books offered me as a child derived from my wretchedness then. Apart from the classics, like The Wind in the Willows and Alice in Wonderland, I was spellbound by the Narnia series, but also by earlier children’s reading such as the E. Nesbit tales in which I was completely absorbed. My life was so saturated with depression that these fictions became a vital escape from it. Of course, the lack of balance or of accord with a normal boyhood that ensued from this distraction meant that I never kept up with my contemporaries in their progress to adulthood. It seemed to me that I always evolved a few steps too late to benefit from conditions for which they were already equipped. While they were daily dealing, more or less successfully, with some unavoidable fact of life, I was still hiding in my room behind Five Children and It.

This attachment to imagination was most obvious later, during my quests for employment, when I had almost to tear away the cobwebs of unreality before I could face up to the practical demands which would be made of me, in positions which I was ostensibly seeking. In fact, my motivation during interviews was

never wholehearted, and this may have been apparent to prospective employers. If I managed to get a job, my self-consciousness and general awkwardness around people prevented me from joining the crowd at work; my hopeless shyness around

women prevented me from declaring my interest in them.

My most familiar memories are not of joy or contentment, but of embarrassment and humiliation. I suppose I’m not a bad looking sort of person, but I have always found my reflection to be a challenge. My body is just my shell, a carapace. It carries my mind, and it often lets me down; I’ve already said too much about it. Some damn fool of a doctor told me just the other day that I should love my body. He was not the right person to tell me this, as he had managed to disfigure this very body through his clumsy intervention to correct a hernia, as well as being a rather impersonal little Swiss surgeon into the bargain, striving, I daresay, to fulfil some semblance of the Hippocratic Oath. Otherwise, I might have taken his advice seriously.

***

So there has been some continuity in my life after all. Continuity without progress. The late or very late realization about how I ought to have reacted to

certain situations or opportunities over fifty years ago still haunts me. I keep asking myself: have I caught up now? Am I now able to judge adequately what may happen to me — am I in sync with my time? I would be glad to get a handle on whom I have become. For most people, one supposes, life is about becoming. Goals present themselves anew throughout active life. Ranging from shopping, through personal improvement, simply to staying alive, these goals provide incentive. Is it usual to lose one’s goals at a certain time of life? The naivete of youth, when all seems possible, eventually gives way to the cynicism of old age, when nothing seems worth the trouble. So, are they driven out of one by age and weakness? Take staying alive. I’m getting tired of fighting gravity. Recently, it occurred to me that I would prefer to contract some terminal disease, whereupon I could resign myself to dying within a given time, providing I could die at

home— rather than to experience repeatedly an enervating new emergency which forces me to spend a few more days in hospital, as a dupe of the sick people business.

I have tried to join the world — against my deepest misgivings. I have achieved none of the things I wanted to achieve.”

What Alter Rebbe said about truth at the end of his life? Why the flat circle?

Lebendige Vergangenheit - Emmi Leisner:

For clarification sake, Both of Yehudi’s sisters were married to Jewish men. Hephtzibah was married to Richard Hauser. He was a Jew turned Quaker. She had one child with him and two with her former non Jewish husband. Yalta was married to Benjamin (Rosenberg) Rolfe. They had two children.

Moshe and Marutha tried to break up both these marriages. Seems they didn’t want more Jews in the family.

Pointing out the spiritual end of the Schneerson clan is important.

Alas our Chasidic brothers count any and all grandchildren of a Rebbe as holy,which is clearly absurd.

So too studying grandchildren in the Schneerson clan whose ancestors have not been observant for 2-4generations is an exercise in futility.

Pres Obama is a desc of Jefferson Davis a true statement,what does it prove.?

If one shows that immediate family members behaved in the manner of the Menuhins,there are lessons,but otherwise we all are grand children of great people and it proves nothing in my opinion.