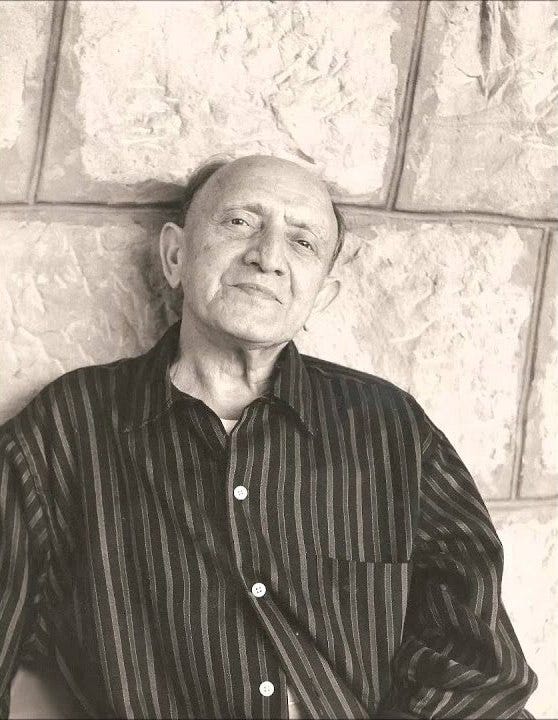

Moshe Menuhin was the father of the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, American-Australian pianist and writer Hephzibah Menuhin, the pianist, painter, and poet Yaltah Menuhin. His wife was Marutha Menuhin (Sher), born in Yalta, Crimea. I guess that’s why they named their daughter Yaltah?

Crimea was the site of the largest karaite community. Marutha’s family allegedly belonged to the Karaite sect? Which technically makes her “non-Jewish” and then the name Sher? Confusing [something fishie in the info on that link].

Moshe was Born in 1893 in Gomel, Belarus. He writes that he was born on 1 of Kislev, 5654. There are some parallels with Zalman Schneerson. Both from Gomel, both had Alter Rebbe and Berdichever yichus. Both approximately the same age. Moshe was 5 years older. So it appears that Gomel had three “Schneerson clans”, this Menuhin, Repker Rov family, and Fishel’s family. By then, you would expect at least a dozen in each of the majors towns in Belarus and northern Ukraine.

Moshe Menuhin wrote an autobiography: “The Menuhin Saga”. What follows is mostly excerpts from the first chapters of the book. In this book, Moshe Menuhin refers to Rashab as “uncle” and says, “he believes” his mother was Rashab’s sister. Did Maharash have a daughter we don’t know about? If you have further details, please provide. It seems from the book that there was closeness to Rashab, but what was the exact relatedness? But let’s not jump ahead. Quotation marks mean a quote from the book.

Update:

Now it becomes clear how little Moshe couldn’t exactly grasp the ins and outs of this inbred family.

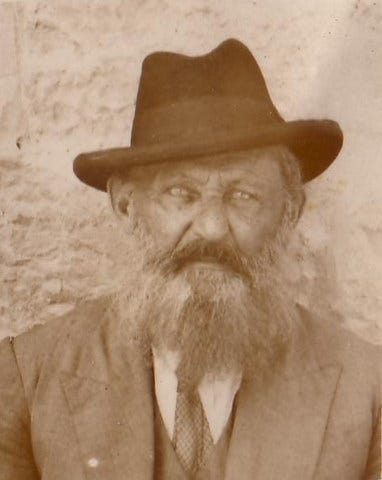

Father

“My father, Yitzhak (Isaac) Mnuchin, was a well-to-do dry goods merchant who had inherited a prosperous family business when his own father had retired to spend his last days in the Holy Land. Grandfather Mnuchin was a great-grandson of a famous Hasidic rabbi, Rebbe Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev…

...On my fourth birthday, my father died. He was only thirty-two. I have almost no memory of him except that I recall that when his body was placed on the floor of our living room, shrouded in white sheets, with candles burning at his head. I happened to ride into the room on a tricycle that I had just been given for my birthday. Someone ordered me to stop. I obeyed, but without understanding what I had done wrong.”

Family

“My mother was left with three children beside myself: her elder son,

Layvik, and two daughters, both older than me, Mooshkeh [this must be the Lubavitcher Muska] and Shandel. Mother sent Layvik and Mooshkeh to Jerusalem to live with the Grandfather Mnuhin [that’s how they used to spell the ordinal name], but Shandel, my younger sister, remained with us in Gomel”

“Baseball” in Gomel

“When I was about eight, I nearly brought a pogrom on the Jews of Gomel - or so it was feared in the district. Late one Friday afternoon, I was playing in the street outside our house with a six-inch pointed stick, which I balanced on a heap of earth or a cobblestone and then hit at one end. When it rose in the air, I hit the stick with a home-made bat. On one of these exercises, the stick flew clear across the wide street and smashed through the window of a government official who lived opposite. I nearly died on the spot from shock and fright. My playmates ran away and, within minutes, our neighbors were locking and bolting their doors and windows as rumors spread all over town that a pogrom would surely break out as a result of my “crime”. But then an unexpected thing happened. The government official| appeared at our door that evening, knocking gently. 'Let me in, please. Do not be afraid.' Trembling, my mother opened the door. The official entered, took off his hat, and gave us a friendly smile. 'The Jews have nothing to fear,' he assured her. 'Nothing is going to happen. All you need to do is to pay for the damaged window.' This good Gentile meant his reassurances sincerely. There had not been a pogrom against the Jews in Russia for more than seventeen years. He was not to know that one would be launched in Gomel itself two years from the time he spoke.”

Mother’s Second Marriage

“It was not considered good for my mother to remain unmarried for very long after the death of my father. She had put off a decision for four years, but now she was considering a proposal, probably from relatives, that she marry a grain broker and fruit dealer called Israel Libo. He lived at Ekaterinoslav (now Dnepropetrovsk), 325 miles (523 km) south-east of Gomel. He was a widower with four children who lived at home with him. He claimed to be a follower of the celebrated Lubavicher Rabbi of that time, Rebbe Shalom Dov Baer Schneersohn, who was my mother's brother, I believe.”

With Rashab in Lubavitch

“My mother took me to my uncle's seat, the town of Lubavich (Lubavichi), to introduce me to the life of his court. She also wished to satisfy herself that Mr. Libo was a bona fide Hasid, who followed the Lubavicher rabbi's code of behavior, prayers and philosophy, including the singing and dancing, and not one of the Misnogdim, the non-Hasidic Orthodox Jews who pursued a more sedate way of expressing their religiosity and communicating with the Almighty, devoting themselves above everything to theological scholarship.

Lubavich lay to the west of Smolensk, 170 miles due north of Gomel. We travelled there on an overnight train and I remember sleeping high up on the third or fourth bunk, which was really more like a shelf. A covered wagon, with a well-dressed Gentile coachman, awaited us when we arrived the next morning at the closest railway station to my uncle's court. We drove for two or three hours through forests and small villages. I was particularly excited by the sight of the great rabbi's fine horses pulling us along, their coats glistening, their nostrils snorting. I could at last see what was meant by the term 'fiery steeds'.

His Eminence greeted us and soon I was surrendered to the life of his court, which was just as I had imagined a king's would look. It encompassed acres and acres of land, with gardens full of flowers and places for animals of all kinds, except pigs. All were taken care of by Gentiles: a Hasid should not do such things. To have a Jew milking cows, as the character Teyve is depicted as doing in 'Fiddler on the Roof', was exceptional, if not unknown. We spent several months at Lubavich, where I was known as the rabbi's einikel (grandson) because of my descent, through my mother, from the founder of Habad Hasidism, Shneur Zalman of Liady, who was actually my grandfather's grandfather's grandfather. I became the bewildered object of veneration by Hasidim attending or visiting

my uncle's court. At mealtimes, between ten and twenty people would be sitting at the rabbi's table. We were waited on only by Jews. God forbid that we be

waited on by goyim. Everything had to be kosher in every sense of the word. For a goy’s hands to touch a bottle of wine, even a corked, sealed bottle of wine, would make it tref, and a Jew would not be allowed to drink the wine inside it.

Course after course was served, the plates piled high with fish, meat and other good things, far more than I could consume. But this was deliberate. After the closing prayers had concluded, my uncle's guests would seize the left-over food from my plate (the shirayim fon ein rebbesohns einikel ) as well as from the rabbi's, and wrap it up to take home to their wives and children. They regarded it as in some way consecrated.

There was always singing with the meals: fervent singing of mysterious songs without words, the singers'eyes pivoted upwards as far as possible, towards God. I learned a lot of Hasidic music this way and, when I had a son, nearly a quarter of a century later, I used to sing these Hasidic melodies to him.

Those who were present at meals at my uncle's home in Lubavich also danced rapturously- but not with women, God forbid! Women were not allowed to appear in the dining hall. No, this was fraternal dancing, with the men putting their arms over the shoulders of their fellow dancers and singing as they danced. I also seem to recall a lot of spiritual, embraceful kissing of each other. I suppose this was another means of getting closer to God. Hasidim could not understand how

anyone could pray or eat without singing and dancing - dances full of ecstasy and mystic exaltation to the point where they really believed that they were floating in the air. As the child of a sad, fatherless home, I found it all emotionally fulfilling but also somewhat disturbing. It was not until later, in my grandfather's house in Jerusalem, that I came to appreciate the poetry and philosophy of Habad Hasidism, the humility, compassion and an intimate identification with God in every aspect of daily life, that accompanies the rapture and joy of the singing

and dancing.

Despite the excitement of the occasions for singing and dancing to the glory of God, the most joyful activity for me as a little boy in Lubavich was kite-flying outside the town with the children of some of my uncle's Gentile servants. I did not have to go far to get out of town because my uncle's lands bordered the edge of town. I had been told not to talk to goyim but, I must admit, I was a rather

peculiar Jew. I did not hate goyim and I could see no persuasive reason for not talking to them. I was not even opposed to eating something that was not kosher. My elders would have been very disappointed in me, perhaps irate, if they had known. They never got to know because I never did it within the boundaries of my uncle's court.

One day, at the edge of town, some Gentile boys beckoned me and asked me if I wanted to fly kites with them. I agreed and went to my uncle's house to find the materials for a kite: some sheets of thick paper, a little flour to make glue, some sticks that could be flattened, and some heavy wool thread from a ball of yarn in my aunt's room that was used for mending socks. Borrowing a sharp knife from the kitchen, and taking along some salted herrings, filched from a barrel behind it, we set off for the potato fields on the town's outskirts. There, with the help of my new friends, I made a splendid kite for myself. Its tail was right; its mount was right; and it soon rose high in the sky, floating beautifully on the air currents.

Because I knew only a few words of Russian and they did not know Yiddish or Hebrew, our conversation throughout this and later kite flying episodes was very limited, but we got along fine. We wrote messages on pieces of paper, punched a hole in the centre of each, strung them on the cord of the kite, and sent them spiraling to the top. We called them 'telegrams'. While I had been making my kite, the other boys had been preparing a fire, putting potatoes to bake in the hot earth beneath, and the herrings on top. When they were all properly cooked, we had a little feast, the memory of which still makes my mouth water.

As one of the Chosen People, my Orthodox conscience should have told me that I was committing the crime of crimes, keeping company with shkotzim, but those were always happy hours for me. In fact, when I think about it, most of my childhood pleasures were found in my play with shkotzim.

That idyll was not repeated for very long, for, satisfied that Mr. Libo would make a religiously suitable husband, my mother announced her decision to marry him. We returned to Gomel to collect Shandel, and were soon on our way to Libo's home in Ekaterinoslav. Our links with Gomel were forever broken, and we missed being there for the pogrom of August 1903 - thank heavens!”

Gerard Menuhin -“Lived it Wrong” in the Flat Circle

In the previous post, we described Moshe Menuhin and his yichus. Gerard is the grandson of Moshe Menuhin and the son of Yehudi from his second marriage. He wrote the autobiography, one can relate to the title. When I bought this book, Amazon immediately suggested another book by Ron Unz. Hey Amazon AI, Ron Unz is also a “Holocaust denier”,…

Thanks! Very interesting. And what a family!

By the way , in my childhood I played such “baseball “ it was called: цурки-палки. (Tzurki-Palki)

R Zalman’s mother was Liba Leah, the sister of Yitzchak Issac Menuchin. Aka, two Menuchin siblings married great-grandchildren of the Tzemach Tzedek