On the subject of Chabad and Wiener Libraries, the Archive of the Rayatz.

Did Rayatz take any books, manuscripts when he escaped Warsaw? Yes, he wanted too. And definitely didn’t take any. Quotes from the book tagged “library”.

Bryan Mark Rigg. “Rescued from the Reich: How One of Hitler's Soldiers Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe”.

I don’t think Rigg knew about the difference between Chabad and Viner libraries when he wrote the book. No one knew. And given that it was Viner and not Chabad library, it’s difficult to understand the Rayaz’s zeal. During the Holocaust, no less. I have no idea what is the origin of the manuscripts in Chabad library in NY (Barry Gourary Memorial Library) before 1978 or even before 1950. I don’t know if they had any.

1927: “The Rebbe immediately left Russia with six followers and his whole family plus his possessions and large library. Everything together occupied four train cars. Two days later, the Rebbe’s party arrived in Riga, Latvia. Once in Riga, he began to transfer his vast library to Poland.”

(p. 34).

“Late on 4 September, realizing it was growing dangerous in Otwock, he changed his mind and went to Warsaw with his family and a group of students in the hope of traveling on from there to Riga. The Rebbe felt terrible forsaking thousands of his fellow Jews, but he knew that only from Riga could he conduct rescue operations1. Tears streaming down his face, he told those who remained behind, “"Be well, everyone, and accept upon yourselves the yoke of Heaven. The king guards his subjects, and you, Jewish children, may Hashem [God] guard you wherever you will be, and us, wherever we will be.”2 The Latvian consulate in Warsaw had sent a private car with foreign license plates for the Rebbe’s thirty-mile trip to the capital. He took the most valuable Lubavitcher manuscripts, regretting that he could not take his “household effects and the entire Library,” which numbered some forty thousand texts.”

(pp. 40-41).

“The Rebbe, remarkably, seemed concerned most about his library. On 27 November, he sent Lieberman a telegram explaining that he lived in horrible conditions and had “no dwelling now, and find myself in the home of friends with the whole family in one room, and therefore have no place for the books.” The Chabad library seemed as sacred to the Rebbe as his own life. In his telegram to Lieberman, he specifically asked that the authorities not only rescue his staff and family but also help move his “valuable library.” The Lubavitchers valued these books, some 40,000 volumes, at “about $30,000” and wanted the United States to obtain permission from the German consul in America for their removal.”

(pp. 115-116).

“This talk about saving books was premature, however, as the visas had not been issued. To convince those in Riga of the Rebbe’s status, Rhoade asked people like Senator David Walsh of Massachusetts and Secretary of State Hull to forward requests to the American consulate in Riga: “Shall appreciate favorable consideration of applications of Renowned Chief Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn and Associate Rabbis World Chabad hierarchy for non-quota visas.”

(p. 136).

“Pell explained to Rhoade that he would have to prove the library was American property. This task would prove daunting. And even though the Rebbe argued that the books were essential to the movement, he could not make the same case for his jewelry and what turned out to be his pots, pans, silverware, and other household items—things he also wanted to get out. Back in Riga, the Rebbe remained agitated about the status of his precious library. He wrote Jacobson on 26 December 1939, saying, “Surely I will receive within a few days a detailed letter about all that has been done for the saving of my library and about taking it out From there.... There are about a hundred and twenty boxes of books and three boxes of manuscripts of our revered and holy parents, the saintly Rabbis... and you will surely do all you can to bring them to your country. There are also the remainder of our other valuables that was left over after the great conflagration...the jewelry, etc.... I have already advised several times by telegram, and also my son-in-law [Gourary] has spoken with you several times over the telephone about the books and the manuscripts and you have as yet not answered anything. I repeat and say again and request most earnestly that you kindly hasten this matter as soon as possible.” Since some of the manuscripts documented Lubavitch history, the Rebbe considered them essential to the preservation of the traditions of his people.”

(pp. 133-134).

“The Rebbe had not experienced ghettos or concentration camps and thus may not have recognized the need to focus exclusively on saving lives that seems so clear today. He simply wanted to be free of Nazi persecution. Only in hindsight do the Rebbe’s efforts to save his personal possessions seem perplexing. His actions should not be construed merely as shortsighted or selfish: he believed them necessary for the continuation of his work. He probably did not think that the money and effort expended for his books and possessions would interfere with his ability to help people in need. He paid three hundred dollars for a lawyer in Poland and probably several hundred more for packing, storage, and shipping. It is unlikely that he viewed saving his library and saving Jews as mutually exclusive efforts. Yet even the famous Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva noted Yohanan’s mistake in not asking the Romans to save Jerusalem in addition to his students and library.”

(p. 135).

“But the Lubavitchers were not satisfied merely to save the lives of the Rebbe and his staff and family. At a time when few Jews in Nazi-occupied lands were being saved, they still wanted to rescue the Rebbe’s books. On 22 January 1940, Rhoade told Kramer that unless Chabad could prove that it held “title to the library,” he could not approach the authorities for it. The documents showing title never materialized, and even had Rhoade received them, he would have had somehow to get the books out from under the Nazis.

The Rebbe refused to give up the fight. On 7 February, while waiting in Riga, he was informed that Jacobson had been unable to effect the rescue of the library. He hired a lawyer in Warsaw to arrange the shipment of 135 to 145 cases of his books and 11 cases of household goods from Poland to New York via Italy. The Nazis would not allow all his possessions to be returned to him. The SS commander in Warsaw would later notify the commissioner for the ghetto that “Rabbi Schneersohn’s cases, which included his crystal, china, and silver, were considered unregistered Jewish property” and therefore subject to forfeiture.”

(pp. 144-145).

“As the Rebbe did not have his library, he soon borrowed or bought several religious books. He then spent long hours reading at his desk amid huge stacks of them. Some have argued that he was trying to find an explanation for the explosion of violence in Europe.”

(p. 155).

Here is the entire chapter of the escape so you understand how it went down. As you can see, no way they took any stupid books with them. Possible couple of bags of manuscripts. But that’s it.

It’s a burden on people who claim there was a big library in NY before 1950, even before 1978, to explain a possible path. How and what exactly?

The Flight

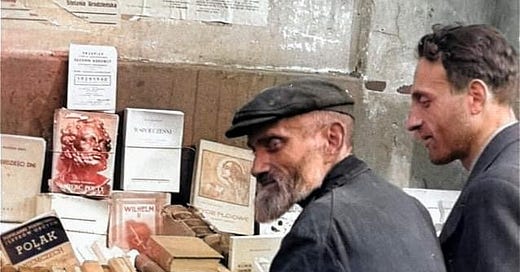

“Having gone to such extraordinary lengths to locate and rescue the Rebbe, Bloch was shocked to learn that the Lubavitchers expected him to arrange for the escape of more than a dozen additional Orthodox Jews, not the few family members he had been ordered to help. Although the Rebbe was a “great leader,” Bloch told Schenk, in his own community he lived a life “totally divorced from reality.” The Rebbe failed to see that he was not in command of the situation. He simply could not understand the hazards he would bring on himself, as well as on the soldiers sent to protect him, if Bloch was forced to escort a large group of Orthodox Jews back through Nazi-occupied Poland, much less through Germany. Bloch was also surprised by what he considered the irrational complaints of the Lubavitchers. For instance, when he returned after his first meeting with the Rebbe with cheese, bread, and sausages for them, they refused the food because it was not kosher. Bloch was dumbfounded. “These crazy people,” he grumbled, “they are hungry and sick. Indeed, a strange people—they don’t even know when somebody is trying to help them.” Schenk regretted not having told Bloch to tell them the meat was beef. (Of course, they wouldn’t have accepted nonkosher beef either.) There had been confusion as to the size of the group in the United States as well. For example, in late November, in a conversation with Rhoade, Pell expressed surprise that Rhoade assumed the Germans would save all of the Rebbe’s entourage. Pell explained that “up to the present there had been only the question of the Rabbi. My request to Herr Wohlthat was made in behalf of the Rabbi and in his reply he had extended that to include the Rabbi’s wife and child.... A request to extend Wohlthat’s action to include a large number of people might prejudice the whole affair.” Rhoade pleaded with Pell to at least ask Wohlthat if he would do so. Pell refused, fearing he might “react unfavorably against the Rabbi.” Soon after the conversation with Rhoade, Pell started to push for the entire group. Probably Rhoade’s aggressive tactics convinced him to ask Wohlthat to include them, which Wohlthat in fact did. Bloch procured a truck and wagon to transport the Lubavitchers to a railroad station outside Warsaw. Here they would board a train for Berlin, and from there one for Riga. Wohlthat’s office had already received funds for Schneersohn’s travel and by 13 December had arranged for him and all his dependents, except for Mendel and Sheina Horenstein, to travel directly to Riga. (Since the Horensteins were Polish citizens, they could not leave Europe owing to U.S. restrictions.) The operation required the coordinated effort of a number of people; Bloch needed a truck, fuel coupons, and train tickets. He also had to arrange clearances to pass through military and SS checkpoints and special approval for “foreigners” to enter Berlin. Only two months after the rescue requests to Wohlthat, the U.S. embassy in Berlin reported on 22 December 1939 that Rebbe Schneersohn as well as his family and some of his followers had left Warsaw for Berlin and Riga. The report failed to describe the difficulties Bloch and his team faced in transit. Before leaving, Bloch advised the Rebbe’s group that they would have to follow his exact instructions, warning that many times he might have to handle them roughly to prevent SS members or other Germans from becoming suspicious. In a dire emergency, he might have to touch some of the women, he explained, although he would do his best to avoid that insult to their beliefs. As they left the building, the Lubavitchers must have felt nervous excitement at finally escaping Warsaw. As they entered the street, passersby must have wondered why a German was leading off this group of Hasidic Jews. Were they to be killed? Although Warsaw had returned to a semblance of normality, with people again at work, it was an occupied capital dominated by the Nazis. As the Jews stepped onto the waiting wagon and truck, Polish children watched them and ran their index fingers along their necks to signify execution. Schenk brushed the children away and reassured his charges that they had nothing to fear. They carried their suitcases and religious books and cast their gaze downwards. A few of them held hands and whispered to one another quietly. Only yards away, the hard clanging sound of marching troops echoed through the streets. It was an SS unit, armed with rifles and side arms. The skull-and-crossbones insignia sparkled on their black uniforms. As the group approached, Bloch considered the possibilities. If the SS was after the Rebbe, he and his men could not defend the people under their protection. Suddenly, Bloch yelled, “OK, you pigs. Get in the truck and wagon. I said now.” Schenk started herding the Jews roughly onto the truck and the horse-drawn wagon, yelling, “Faster.” The SS unit marched by without paying much attention. Bloch rode in the truck with the Rebbe. Along the road, they observed the charred remains of Polish armored trucks and troop carriers, carcasses of horses, and the fresh graves of civilians caught in the maelstrom of war. Schenk later recalled that the Rebbe looked out at this horror, shook his head, put his old, wrinkled hand to his face, and rocked back and forth mumbling to himself. When they reached the first checkpoint outside the city, the SS asked Bloch to step out. Bloch presented his papers and then carefully viewed his surroundings. He scolded one SS soldier for not saluting properly. Schenk heard the man apologize halfheartedly. Picking up on this, Bloch took out his notebook and asked for the names of the man and his superior. The man knew he was in trouble. As two soldiers busied themselves with Bloch, another two walked up to the group in the wagon. One looked at what must have been for him a group of strange people. In the young man’s blue eyes, Schenk saw not hate exactly but a fierce curiosity. He asked Schenk who these people were. Schenk told the man that all questions should be directed to Bloch, his superior. “What unit are you with?” the SS man demanded. Schenk replied, “We are members of the Abwehr.” The young man’s eyes opened wider, then he turned his gaze to the ground and returned to his post. Bloch walked back to the truck, breathing heavily. He looked at Schenk and said, “We made it through this one. I told them these Jews were prisoners sent for by special authority in Berlin. They seemed to want no further explanation. Anyway, the Wehrmacht should be at these checkpoints, not the SS.” Bloch looked back at the guards as the truck started up and moved slowly through the opened field gate. Instinctively, he placed his hand on his pistol. At some point, the Rebbe again asked Bloch why he was rescuing them. When Bloch told him he was half Jewish, he asked if Bloch felt Jewish. It must have seemed odd to talk to this man who looked like a character out of the Bible and try to understand why he had asked such a question. Surely taken aback, Bloch probably hesitated. Then he told the Rebbe that he did not but that he had always been intrigued by his Jewish past. “You have a strong Jewish spirit,” the Rebbe responded. The fact that Bloch was rescuing him seemed to verify Bloch’s Jewish loyalty for the Rebbe, who saw him returning to his roots in performing this brave act. Bloch most likely did not reciprocate the Rebbe’s feelings of kinship; he simply performed his duty to the best of his abilities. The Rebbe felt, however, that God was conducting the whole event, and what better instrument to use than a fellow Jew. Also, as one Lubavitcher rabbi explains, the Rebbe believed that praising someone could help that person rise to future challenges; creating a bond with Bloch might make Bloch more effective in taking the next steps in the rescue. The motley group passed columns of soldiers and military trucks, some with the large white SS runes painted on their sides. Despite the horrors and dangers surrounding them, the Lubavitchers remained focused in their faith. Some tried to convince Schenk that their way of worshiping was the best way to observe God’s laws. As Schenk understood their argument, a harmonious world would arise only when all Jews recognized their Rebbe and his doctrine. Once this unity was achieved, the Messiah would come. The Lubavitchers thanked Schenk and the other Germans for ensuring that the world would not lose its greatest living leader, who held “mankind’s destiny in his hands.” One checkpoint right outside Warsaw proved particularly difficult. As the truck started to go through the inspection process, an SS soldier shouted at Bloch, pointing his finger at the Rebbe. The SS were confused. They looked at Bloch, an officer, then they gazed at the Orthodox Jews whom they had just forced to step out of the truck, surrounding them with rifles lowered. Although the sky was a light gray, the shadows of the soldiers danced around the Jews, who kept their eyes to the ground. Several SS men pointed their rifles directly at the Rebbe’s face. Schneersohn’s hands shook. Bloch told the SS commanding officer, a tall, ordinary-looking man in a jet-black uniform, that he had special orders to take these Jews to Berlin. The SS officer sniffed, blinked, and shook his head, saying he was shocked he had not been informed about this cargo. He threatened to detain the Jews and hold Bloch and his men at his headquarters until he received authorization from Berlin; the whole thing “smelled rotten” to him. “Why does the Abwehr care about Orthodox Jews?” he asked, gesturing toward the group. “They are ignorant scum who should be shot.” Then he turned back to Bloch and asked, “What are you really doing?” For a moment, Bloch feared the SS had been informed about the mission. He felt that he was about to lose the group and possibly his own clemency. A sweat broke out across his shoulders and his breathing became more rapid. He later told Schenk that if the Berlin SS had known that he, a half Jew, was helping over a dozen Orthodox Jews escape Warsaw, they would have had his head delivered on a platter. “I don’t understand why these Jews are being taken to our capital,” the SS officer insisted, his face reddening with frustration. “Secondly,” he continued, “I don’t like taking orders from an army officer who is incapable of telling me why these creatures are being escorted to Berlin or who has ordered him to take them.” The SS man ended his diatribe with a malevolent grin. Bloch’s fists clenched and the blood rushed to his cheeks as he shouted harshly that Canaris had issued his orders. He had contact with several regiments in the area, he said, naming them and their commanding officers. If the SS man did not let the group through, he would personally see to it that he was arrested and “properly dealt with.” The officer starred at Bloch, summing up the gravity of his threat. After some uneasy hesitation, he ordered the roadblock opened and let Bloch’s group through. The bluff had worked. A few miles past the roadblock, Bloch told the Rebbe everything would be all right, adding, “The SS is not Germany.” The Rebbe did not look persuaded. Schenk registered the deep irony of their situation. Here were SS personnel who wanted to kill the Jews, and Wehrmacht soldiers who wanted to help them—and both groups were German. In fact, many of the Lubavitchers believed Bloch was not a real German officer but a Jew playing soldier to save the group. The Rebbe probably recounted this horrible scene to his secretary, Chaim Lieberman, who later wrote: “As soon as they saw us, the German soldiers were as bloodthirsty as wild animals to hurt our group of Jewish men with beards and side locks.... A German Jew who had served in World War I and wore a uniform covered with medals helped the Rebbe and his family escape this danger.” Bloch, the World War I veteran, obviously told the Lubavitchers about his Jewish father to calm their fears and perhaps even because he felt, in a strange way, akin to them. The fact remains that they believed a fellow Jew was rescuing them. Some saw Bloch as a guardian angel sent by God. Perhaps this idea struck them as more plausible than that of a “friendly Nazi,” and more in keeping with the stuff of their faith. Viewing these rather unusual Germans as acting under God’s command would not have been unusual for the Lubavitchers. At the train station, Bloch’s group again attracted the attention of the authorities. An army officer questioned him as to why Jews had been issued first-class tickets. Bloch or one of his men may have told him that the Jews were traveling under diplomatic protection and then said a few other things that caused him to leave without further questioning. Sitting in a train full of Nazi officials and military personnel made the Jews uncomfortable. One can only wonder what they felt as they crossed the border into the Greater German Reich and passed through towns bedecked with swastika flags. This was not their world. As one Lubavitcher described it, they were now in the “very heart of the evil Nazi kingdom.” 14 On 15 December, Bloch brought the Rebbe and his group to Berlin, where they stayed one night at the Jewish Federation. They probably picked up the visas there that would ensure their escape. The next day, they boarded another train, again in a first-class cabin, for Riga, accompanied by their German escorts and delegates from the Latvian embassy. When asked why Jews were traveling in the first-class section of the train, a “German officer,” most likely Bloch, was reported to give the same response as earlier, that they were traveling on diplomatic orders and should be left alone. At the Latvian border, the Germans bade the Jews farewell. It was probably the last time Bloch saw the Rebbe. As they left German soil, the Rebbe and his group rejoiced. “We felt so good once we reached the Latvian border,” Barry Gourary says. On its way to Riga, the train stopped at Kovno (Kaunas), where several of the Rebbe’s followers met the train and danced with joy as he arrived. He had returned to his world.”

Rigg, Bryan Mark. Rescued from the Reich: How One of Hitler's Soldiers Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe (pp. 127-129). Yale University Press.

P.S. It’s a great shame the Lubavitch doesn’t have a closet somewhere named after Admiral Wilhelm Franz Canaris, or Major Ernst Bloch.

Of himself and his pots and pans.

I will run, and you will be left here to die. “Accept upon yourselves the yoke of Heaven.”